Driverless Cars Hit a Bad Patch

Suspension of the Cruise robotaxi service in San Francisco, following a serious accident, has raised questions about the safety and feasibility of driverless cars. We look at the promise and the problems of autonomous driving.

Driverless cars have been with us much longer than you may think. Some will say the history stretches back to Leonardo da Vinci, but for most of us, Tesla’s introduction of a semi-autonomous autopilot feature is where driverless cars really started.

In less than ten years, the driverless car has come a long way, but the technology has also hit more than a few speed bumps. Most recently, the rollout of driverless taxis in San Francisco, California, came under scrutiny when a Cruise robotaxi from General Motors (GM) hit and dragged a pedestrian.

The accident led to the immediate suspension of the service and GM could face over $1 million in fines, but it has also stirred up a number of wider questions about the industry. Not only did it reveal serious limitations to the vehicles’ autonomous driving capabilities, but it's unclear whether this is a temporary setback or if the current technology is fatally flawed.

A primer on driverless cars

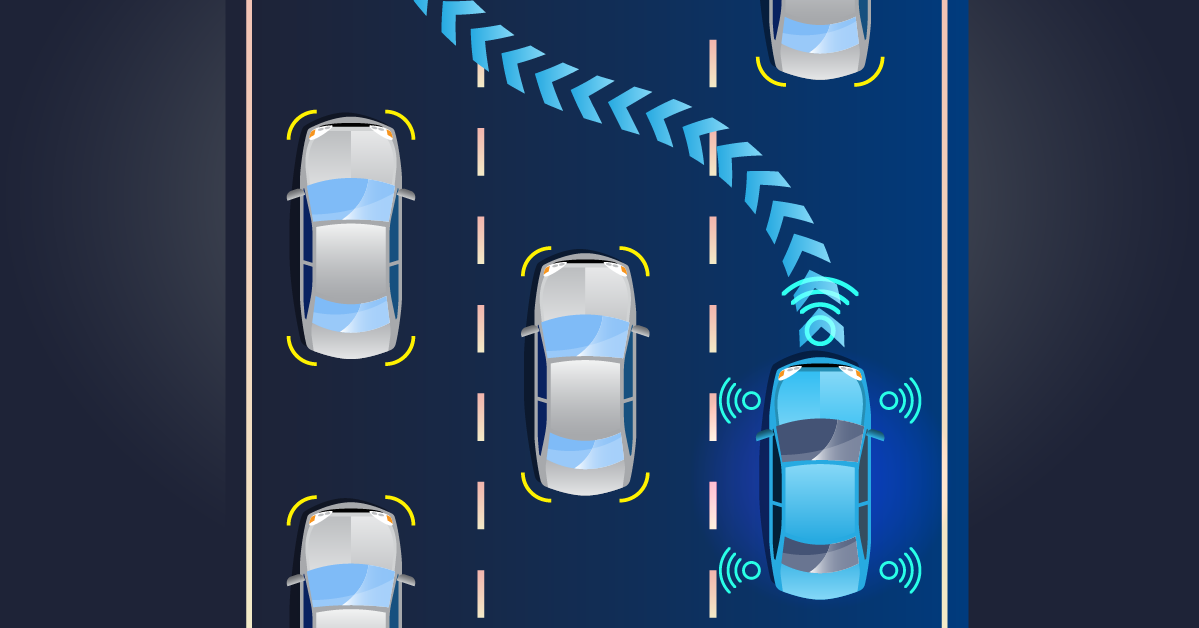

First things first, let’s define what a driverless car is. Self-driving vehicles do not require human drivers to operate the vehicle. Sometimes called autonomous cars, they use a combination of sensors and software to control the vehicle.

There are different degrees of autonomy, from a few automated features like 'adaptive cruise control' to fully independent operation, known as Level 5. A partially autonomous vehicle needs a driver to intervene in the face of obstacles or uncertainty, while fully autonomous Level 5 vehicles often don’t have a steering wheel.

It may be hard to imagine — especially given the limitations we will discuss in the next section — but many believe a future filled with fully autonomous vehicles will be safer. However, as Roxane Googin, Chief Futurist at Group 11, said on the Deep Takes, Not Fakes podcast, that future may not come until infrastructure allows drivers to relinquish control to a centralized system designed specifically for autonomous vehicles. As The Washington Post’s Megan McArdle puts it, “This world will undoubtedly be safer than the current one, and ideally, future generations will view traffic fatalities the way we view cholera: as a quaint abomination. But first, humans and computers will have to share the roads without always understanding what the other is doing.”

How do self-driving cars work?

Each self-driving vehicle is different, but most of them operate using the same basic tools. As the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) explained back in 2017, “most self-driving systems create and maintain an internal map of their surroundings, based on a wide array of sensors, like radar. Uber’s self-driving prototypes use sixty-four laser beams, along with other sensors, to construct their internal map; Google’s prototypes have, at various stages, used lasers, radar, high-powered cameras, and sonar.”

From there, UCS explains, software processes the data, plots a path, and instructs the vehicle’s “‘actuators,’ which control acceleration, braking, and steering. Hard-coded rules, obstacle avoidance algorithms, predictive modeling, and ‘smart’ object discrimination (ie, knowing the difference between a bicycle and a motorcycle) help the software follow traffic rules and navigate obstacles.”

It doesn’t take a software engineer to imagine the problems that might arise — and, in fact, you don’t have to imagine them at all.

Trouble with driverless cars

The widespread rollout of driverless taxis in San Francisco has given the public a first-hand look at the limitations of AI-powered cars. From gridlock caused by about a dozen taxis that lost internet connectivity and simply stopped, to another car that drove straight through the orange cones and into a construction site, it's clear the technology has room for improvement. As The Los Angeles Times Editorial Board points out, “In theory, this compendium of mistakes in San Francisco is making the technology better and safer for the future. But that ignores the effect the vehicles are having right now.” In some cases, that effect has been deadly.

Driverless cars have interfered with first responders more than 50 times, and The New York Times (NYT) reports that “Tesla’s autopilot software, a driver-assistance system, has been involved in 736 crashes and 17 fatalities nationwide since 2019.”

The limits of AI technology

Part of the problem lies within AI technology, which essentially uses the same predictive modeling as ChatGPT to make guesses about what is happening on the road and the best response. As Spectrum observes, “Neither the AI in LLMs nor the one in autonomous cars can ‘understand’ the situation, the context, or any unobserved factors that a person would consider in a similar situation. The difference is that while a language model may give you nonsense, a self-driving car can kill you.”

At the same time, doubt has been cast on how autonomous the vehicles are in practice. The New York Times

reporting on GM's San Francisco fleet said: "Those vehicles were supported by a vast operations staff, with 1.5 workers per vehicle. The workers intervened to assist the company’s vehicles every 2.5 to five miles, according to two people familiar with its operations." If this continues to be the case, it suggests that the operation's business model is not sustainable.

Meanwhile, legislation could help, but so far, it’s nowhere in sight in the U.S.

Who's responsible?

In California, responsibility for regulating robotaxis is split between two state agencies — the Department of Motor Vehicles and the California Public Utilities Commission — taking the control out of the hands of municipalities dealing with the reality of these vehicles. Things are not much better at a national level in the U.S.

NYT reports, “There are no federal software safety testing standards for autonomous vehicles — a loophole large enough for Elon Musk, General Motors and Waymo to drive thousands of cars through. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration regulates the hardware (such as windshield wipers, airbags and mirrors) of cars sold in the United States. And the states are in charge of licensing human drivers.” But no driver's test is administered when AI is behind the wheel, and lawmakers are just now looking into new ways to regulate the emerging technology.

Is there a future for driverless cars?

Are the problems caused by the transition to driverless vehicles worth the payoff? Some will undoubtedly say no. In Britain, autonomous cars face a ban. Still, there are some true believers. The Washington Post’s McArdle argues that the growing pains are worth it: “Too many hours, and lives, are currently lost getting ourselves from one place to another. If we want to reach a time when we’re able to reclaim them, however, we’ll need to prepare for some expected turbulence en route.”

It’s telling that most examples of widespread use are for taxi services and not personal use. A 2022 Pew Research study suggests car companies still have a long way to go when it comes to winning over the public: “Roughly six-in-ten adults (63%) say they would not want to ride in a driverless passenger vehicle if they had the opportunity, while a much smaller share (37%) say they would want to do this.”

So, perhaps the most relevant question is whether driverless cars will ever earn buyer trust and make the economics of driverless cars sustainable. On that, the jury is still out.